Sunday, December 26, 2010

New Florida Ag Chief Would Stop Decision on Chocolate Milk

Florida's board of education had been poised to decide whether chocolate milk should be banned from schools because of sugar that contributes to an epidemic of childhood obesity and Type 2 diabetes.

The Orlando Sentinel reports that Adam Putnam, who sill soon take over as head of Florida's agriculture department, has sent the board of education a letter asking for a halt to any move to eliminate flavored milk. Putnam, a former Republican congressmen from a citrus farming family in Florida, will be pushing for his department to take control of food served in Florida schools, according to the Sentinel.

According to the Sentinel, only two other states--Texas and New Jersey--allow agriculture authorities to manage school food. Like the U.S. Department of Agriculture, which oversees the national school meals program, agencies on the state level are charged with promoting agricultural products, including those of the dairy industry.

Critics see this as posing a conflict with children's nutrition. On a national level, the dairy industry currently is engaged in an aggressive effort to promote chocolate and other flavored milk in schools nationwide as part of a congressionally mandated "check off" program that is overseen by the USDA.

Other school districts, such as the District of Columbia, have eliminated flavored milk from school menus because of the strong link between sugar and weight-related health issues. A one-cup serving of chocolate milk, for instance, typically contains at least 26 grams of sugar, more than half of which is added to the milk in the form of high-fructose corn syrup.

Thursday, December 23, 2010

Must Read: Janet Poppendieck Interview

aka The Slow Cook

If you haven't had time to read Free for All: Fixing School Food in American, the definitive guide to how the nation's cafeterias ended up in the mess they're in now, an excellent interview with the author, sociologist Janet Poppendieck, has recently appeared in two parts.

The interview covers a lot of territory succinctly but in enough detail to give a good grounding in the many issues of concern in the school food landscape. The first part is here, the second part here.

Then, read the book and you'll understand why your local lunch ladies need all the help they can get.

Wednesday, December 22, 2010

We're Profiled at Jamie Oliver's Website

By Ed Bruske

aka The Slow Cook

A Google alert tipped me off this morning that the story of The Slow Cook--my story as accidental kitchen gardener, school food activist, blogger--was featured on Jamie Oliver's website yesetrday. Actually, it's a reprint of the article published by Organic Connection magazine, which I posted here earlier this week. Here's the link to the Jamie Oliver site.

Saturday, December 18, 2010

Kids Make Butter Chew Cookies

By Ed Bruske

aka The Slow Cook

Over at The Slow Cook blog, I recently described trying to decode my grandmother's recipe for butter chew cookies and my readers have been on pins and needles waiting to learn the final formula we used in our baking appreciation classes this week. Here goes...

This is a two-step baking process. First you make a dough that will form an underlying crust for the cookie. Then you cover the crust with a chewy topping of brown sugar, coconut, nuts and egg whites.

Start by creaming 1 1/2 sticks room-temperature butter and 3 tablespoons granulated sugar. We did this by hand, beating the butter and sugar together until it was a soft, creamy texture. But you could also do it in an electric mixer. Then stir in 1 1/2 cups flour, completely incorporating the butter mixture. Use your hands to gather and squeeze the mix together into a ball. Place the dough in a greased, 13-inch by 9-inch baking pan and press the dough toward the edges of the pan with your fingers until the pan is completely covered. Place in a 350-degree oven and bake 15 minutes. The dough should be cooked through and turning a little brown around the edges. Set aside to cool.

Meanwhile, separate three eggs into two mixing bowls. Set the egg whites aside. Into the three yolks mix 2 1/4 packed cups brown sugar, 3/4 cup flaked coconut and 1 cup chopped pecans or walnuts. Stir well until egg is completely incorporated.

Beat egg whites until they begin to form soft peaks. Fold into the brown sugar mixture, then spread the mix evenly over the cooked dough. Return pan to the oven and bake another 30 minutes. The topping should be firmly set and mahogany brown. Place on a wire rack to cool at least 45 minutes, or refrigerate overnight.

The trickiest part about these cookies is the cutting. The topping is tender and easily crushed. Use a sharp knife to cut the finished sheet of cookie away from the edges of the baking pan. When loose, invert onto the back of baking sheet, then flip again onto a cutting board. Use a serrated knife to score the topping through to the crust underneath, forming the outlines of individual rectangular pieces about 1 1/4 inches long and 3/4 inch wide. Follow the scoring with a chef's knife, pressing down to cut through the crust. I did this with four rows of cookies at a time.

When the cookies have all been cut, arrange them on a decorative plate and dust with confectioner's sugar. Kids have a great time making it "snow" on the cookies, pouring the sugar into a small sieve, then "spanking" the sieve with their other hand. Or you can dust them with sugar and store in a cookie tin, using parchment paper between layers of cookies.

Warning: these are incredibly sweet and addictive.

Thursday, December 16, 2010

Lunch from Home: Chicken Soup

By Ed Bruske

aka The Slow Cook

There's precious little on the Chartwell's menu that appeals to our daughter anymore. She takes her lunch to school almost every day and she's very particular about what she will eat.

One thing she loves is soup. She swoons over corn chowder, but she also adores chicken noodle. I brought some home from the steam table at Whole Foods. It was pretty thick, so we added a little chicken broth to it.

Remember glass-lined thermoses? They haven't gone completely out of style. I'm still amazed how well an old-fashioned thermos will keep soup hot. This soup was still steaming when daughter opened it at school.

Things she also likes in her lunch: apple slices acidulated with lemon juice (I've learned that some kids grow up like no other kind of apple), "baby" carrots and certain kinds of semi-hard cheese, like this Robusto. And note her favorite Chinese spoon. She wouldn't have her soup any other way.

With a lunch like this, daughter is happy. Of course, you could make her even happier if you threw in a cookie for dessert.

Wednesday, December 15, 2010

What's for Breakfast: 'Crush Cup'

By Ed Bruske

By Ed Bruskeaka The Slow Cook

Here are the remnants of what Chartwells calls a breakfast "parfait" made of yogurt and granola. You could eat it with a spoon--or, in the case of school kids, a "spork." But kids are far to clever for that. They now call this a "crush cup."

Why a "crush cup"?

As you can see here, the cup is lifted with the hands directly to the mouth, where a sucking action pulls the yogurt and granola into the gullet. To maintain flow, you have to "crush" the plastic cup with your fingers.

Hence, "crush cup."

Tuesday, December 14, 2010

Tax Breaks for Billionaires, Higher Lunch Prices for School Kids

By Ed Bruske

aka The Slow Cook

Somehow Congress can find money to give tax breaks to billionaires. But in a little-noted provision of its reauthorization of child nutrition programs, signed into law yesterday by President Barack Obama as part of the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act, lawmakers have told schools to raise lunch prices to at least cover what it views as the full cost of making a meal. Entitled "equity in school lunch pricing," the new mandate could, by increasing prices gradually for students whose families aren't low income, pump an additional $2.6 billion into the school meal program over the next 10 years, according to one estimate.

While that's a much-needed infusion of cash, school food services professionals say the move could have the side effect of driving hundreds of thousands of children from the federally subsidized school meals program. The School Nutrition Association (SNA), representing some 50,000 food service workers across the country, likens the new law to cuts in federal support for school meals enacted during the Reagan years, when participation in the National School Lunch Program plummeted 25 percent among full-price students because schools were forced to charge more -- and ketchup was declared a vegetable.

"When you raise prices, it has a real impact on participation," said SNA spokeswoman Diane Pratt-Heavner. "Our members tell us time and time again, even when they raise prices by just a dime, they see participation drop."

"The downside of raising meal prices during these tough economic times is that you run the risk of making the meals unaffordable for kids whose families just barely miss the financial eligibility cut-off," said Kate Adamick, a school-food consultant who has long complained about the pricing disparity. "This is a significant reality in lower-middle class communities, especially for schools located in parts of the country in which the cost of living is extremely high, such as New York City and San Francisco, to name just two. I think this is the right change that may be coming at the wrong time."

Federal subsidies for school meals are intended primarily to help feed low-income children, who receive meals either free or at a reduced price. Even kids who don't qualify and pay "full price" in the subsidized meal line are actually supported by federal funds to the tune of 26 to 34 cents per lunch. But what most schools charge for a full-price meal typically is less than the federal subsidy, currently $1.48 for breakfast and $2.72 for lunch. For instance, here in the District of Columbia, schools serve breakfast free to all students regardless of their ability to pay, while a full-price elementary school lunch is only $1.25, a high school lunch a mere $1.50.

Free breakfasts and underpriced lunches help explain why D.C. schools rack up $7 million in food service deficits every year, or 25 percent of the entire budget.

Critics argue that underpricing also helps explain why schools never seem to have enough money to improve the quality of the food they serve, and that low-income children should not be short-changed in order to support kids who come from wealthier homes, even though there is nothing in federal law to say that government subsidies can only be used to feed needy students. Food service professionals counter that lower prices attract more kids to the meal line, creating economies of scale and helping to lower the marginal cost of meals served in a program they contend is chronically underfunded.

"We all know the effect of higher prices on people's purchasing decisions, and this basic economics lesson applies to school meals as well," Pratt-Heavner said. The new rule, she said, is likely to fall heaviest on families in rural and economically depressed areas where parents "simply cannot afford to pay the higher school-lunch prices charged in wealthier suburban neighborhoods."

Under the formula approved by Congress, schools that are not charging the full cost for lunch would have to start raising their prices annually by an amount equal to the rate of inflation plus 2 percent. For some schools, getting their prices fully caught up could take 20 years.

A study released in January 2010 by the Center of Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP), a nonprofit research organization focused on low-income Americans, noted that student payments for federally reimbursable meals account for only about one-quarter of school food-service revenues. The greatest share of income comes in the form of federal subsidies, with sales of competitive foods in á la carte lines (often unhealthy snacks like cookies and chips) and vending machines contributing about 16 percent, and state and local governments chipping in another 9 percent on average.

Adamick said most of the schools she visits underprice their meals. "The rationale usually given is that the board of education doesn't want to raise prices because it will be unpopular with parents and may drive down participation (not to mention the liklihood of a board member's re-election). In some districts, the meal prices haven't been raised in many, many years."

A study conducted during the 2005-2006 school year by the USDA, which oversees the school meals program, found that the prices schools charged for paid lunches varied widely, from 65 cents to $3, with the most common price being $1.50 -- well below cost. A more recent analysis by the CBPP of the nation's 20 largest school dischool districts found that the average charge for lunch was $1.80 in elementary schools and $2.14 in high schools, still far less than the federal reimbursement rate.

Houston schools this year experienced what they described as a grave development in their cafeterias. Because of "food prices soaring nationwide," the cost of a paid meal would have to go up: from $1.50 to $1.70.

"School districts generally want to set a price that is affordable for the wide range of families with incomes in the paid meal category," the CBPP concluded. "The disparity results in a revenue shortfall that undermines the goal of providing the highest quality meal possible to all students."

The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities cited a USDA study as showing that student participation in the subsidized lunch program was only 3 percent lower in districts that charged $2 per meal compared to $1.50 per meal. But in a program involving more than 31 million children nationwide, that 3 percent would represent nearly 1 million students.

Said the SNA's Pratt-Heavnery: ""Unfortunately, no one knows how severe the decline in participation will be as a result of [the new law], and that’s a risky gamble to play with a program that is vital to the nutrition and well-being of millions of school children."

This story originally appeared at Grist.

Monday, December 13, 2010

What's for Breakfast: Kix & Muffin

By Ed Bruske

By Ed Bruskeaka The Slow Cook

Over the summer, the food services director for D.C. Public Schools decided to remove flavored milk and sugary cereal from school breakfast menus. The means no more Apple Jacks or Raisin Bran. Instead, the kids are served only cereals with six grams of sugar or less.

According to the General Mills website, these Honey Kix, made primarily of corn, contain six grams of sugar in a 1 1/4 cup serving. Next to it is an "apple cinnamon muffin," according to the Chartwells menu website. It doesn't have any packaging identifying the nutritional content. The Healthy School Act approved by the D.C. council earlier this year requires the schools to post the ingredients in school food. But a website containing that information and promised for November has now been delayed till next year.

Notice also the string cheese on this tray. That's also something new that began in the fall. All in all, this is a big change from the Apple Jacks, strawberry milk, Pop-Tart and Giant Goldfish Graham breakfast--often 15 teaspoons worth of sugar first thing in the morning--D.C. kids were getting as recently as last spring.

The big change had nothing to do with Congress or the USDA or even our own Healthy Schools Act, and everything to do with the bold action of our local food services director. Even though school meals are funded mostly by the federal government, it's much easier to make change at the local level than to wait for Uncle Sam.

Saturday, December 11, 2010

Kids Make Gingerbread Cookies

By Ed Bruske

aka The Slow Cook

Kids turned out in droves for the first of my new "baking appreciation" classes. They've longed for something sweet instead of those nasty old vegetables we usually cook all the time.

Since I'm not a professional baker, I was looking for something fairly simple but also seasonal and appropriate as a dessert for tonight's parents dinner, which has a Moroccan theme. Okay, so gingerbread cookies are exactly Moroccan (at least I don't think so). But spice-wise, they do have a passing affinity with North African cuisine. I'm referring to the cinnamon, of course.

One reason for baking with kids it to teach science and math. The components of baked goods often react with one another chemically in precise ways to yield the products we like so well. Also, we measure much more carefully when baking, hence the need to learn fractions and weights. In fact, weighing ingredients such as flour is more accurate than measuring in volume. So I brought along a scale as well.

Pretty soon, the aroma of our spicy cookies were drawing admirers from all over school.

This recipe comes from The New Best Recipes, from the same people who bring you Cook's Illustrated magazine. It's a big, thick book that's all about taking classic dishes and fiddling with them to come up with a recipe that produces the very best in its class. Thus, the authors discovered that the best gingerbread cookies require a little more fat (butter) than most traditional recipes call for. So we're going with that.

We've halved the published recipe and adapted it by hand, rather than with an electric food processor or blender. But you can certainly opt for one of those gadgets if you prefer. This recipe yields 40 cookies such as those you see above. To make ornaments suitable for hanging on your holiday tree, simply make a hole in the appropriate spot before the cookies go into the oven.

Preheat oven to 325 degrees.

Mix together 7.5 ounces (1 1/2 cups) unbleached all-purpose flour with 2.5 ounces dark brown sugar, 3/8 teaspoon baking soda, 1 1/2 teaspoons ground cinnamon, 1 1/2 teaspoons ground ginger, 1/4 teaspoon ground cloves and 1/4 teaspoon salt. We used a pasty cutter to break up the brown sugar, then crushed any reamaining sugar lumps with our fingers.

Dot the top of the flour mix with 6 tablespoons unsalted butter, cut into pieces. Cut the butter into the flour mix: We used a pastry cutter first, then finished the job with our fingers, rapidly pinching the butter and flour together until the mix resembles coarse sand.

Use a greased measuring cup to add 3/8 cup dark molasses to the flour and butter mix. Add 1 tablespoon milk as well. Stir everything together with a wooden spoon. When all of the ingredients are incorporated, use your hands to form the dough into a ball, kneading it a few times if necessary to create a smooth mass.

Divide the dough in two. Place each half between sheets of parchment paper and roll the dough out to a thickness of 1/8 inch. Lay the dough packages on a sheet pan and place in a freezer for 20 minutes to stiffen, or in a refrigerator for at least a couple of hours or overnight.

When the dough is chilled, remove the top sheet of parchment paper from one piece and invert it onto a floured work surface. Remove the second sheet of parchment paper. Use lightly-floured cookie cutters to create the shapes you like and place them on a greased baking sheet, or on a sheet pan lined with parchment paper. Place in oven and bake until cookies are firm when pressed in the middle with a finger, about 20 minutes.

Use an small, offset spatula to remove the cookies from the pans. When they have cooled, store them in a cookie tin or sealed container, using parchment paper to separate each layer of cookies.

You could decorate these cookies if you like. We'd need another class for that.

Friday, December 10, 2010

What's for Breakfast: Biscuit & Pears

By Ed Bruske

aka The Slow Cook

I've published a photo like this before: canned pears on a whole wheat biscuit.

Something about this--the idea of placing pears on a biscuit--appeals to me. I'd never eat the biscuit myself, since I don't eat starchy foods. But if I were to eat it, I think I'd like it even better with some cream cheese spread on the biscuit. Perhaps even an herbed cream cheese. Or, better yet, and herbed goat cheese.

Am I getting carried away?

Yet, even though I like the concept, I'm not sure how appealing this particular item is. I wonder what readers think. Good idea, or thumbs down?

Thursday, December 9, 2010

What's for Breakfast: Waffles & Yogurt

By Ed Bruske

By Ed Bruskeaka The Slow Cook

All these months I've been writing about the food in my daughter's elementary school and I have to admit, I don't actually taste the food that often. Not that I wouldn't, but the photos I take are of food the kids are eating. I don't have a tray of my own.

But every once in a while daughter comes back from the food line with things she has no intention of eating. For instance, for this breakfast--served free to all students, courtesy of D.C. Public Schools--the only thing my daughter really wanted was the juice. She may have eaten some of the canned peaches.

So I got to try the waffles and I must say they aren't nearly as good as they look. They're really crispy. They arrive pre-made and frozen. Then they're reheated. This year, instead of serving them with high-fructose corn syrup masquerading as maple syrup, the schools are offering yogurt, sometimes a flavored yogurt--such as raspberry--sometimes vanilla.

The yogurt's pretty sugary, but it's certainly better than high-fructose corn syrup. I'm not necessarily opposed to canned peaches either, as long as they're not swimming in a sugary syrup. But what's with the plastic cup? That's an expense the schools could save just by spooning the peaches onto the tray.

Sometimes they do spoon the fruit directly onto the tray. I'm mystified by the decisions food services makes.

Wednesday, December 8, 2010

Healthy Schools Act Saved

Word came yesterday that the D.C. Council had spared the Healthy Schools Act from the budget axe.

While a number of social programs weren't so lucky, D.C. Council Chairman and Mayor-elect Vincent Gray chose not to follow the suggestion of outgoing Mayor Adrian Fenty and use some $4.7 million intended for better school meals to help close a $188 million budget gap.

The money funds an extra 10 cents for breakfast meals, 10 cents for lunches and five cents for every lunch that contains a locally grown product. It also picks up the lunch tab for kids who otherwise are eligible only for reduced-price meals.

Along with the many menu improvements instituted by the D.C. Public Schools' new food services director, Jeffrey Mills, the Healthy Schools Act has helped make a noticeable improvment to kids' cafeteria trays this year.

An aide to D.C. Councilmember Mary Cheh (D-Ward 3) said an outpouring of support for the law helped save the day.

Lunch from Home: Chips

By Ed Bruske

By Ed Bruskeaka The Slow Cook

Parents often say the food at school is so bad, they would much rather pack their kid's lunch at home.

From what I've seen, the lunch kids bring from home often is much worse than what the schools are serving. It's a funny thing what some parents think is appropriate lunch food.

I couldn't help noticing this girl, for instance, who was diving into a plastic shopping bag crammed with an assortment of different chips and cheese puffs.

I suppose the trick is to pack enough different kinds of chips to maintain a child's interest.

Is this anything like what you call lunch?

Tuesday, December 7, 2010

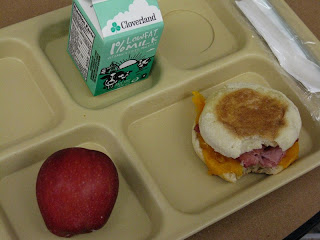

What's for Breakfast: Turkey & Cheese Muffin

By Ed Bruske

By Ed Bruskeaka The Slow Cook

Chartwells calls this "toasty turkeyham and cheddar on a whole wheat muffin."

Our kitchen ladies did a good job of keeping the sandwich warm and I like the turkey ham. Not only was it toasty, but it really tasted like ham.

There's not much you can do with the cheddar. It's grated cheesed that gets piled onto the bread, then melts into a pretty nasty looking coating. I tried to eat it, but I couldn't pull it away from the muffin, which I wouldn't eat on account of the carbs, which I avoid at all costs.

A plan to close a $188 million budget gap here in the District of Columbia would eliminate the extra funding for school meals that had gone into effect this year by way of our Healthy Schools Act. That could spell the end of local fruits and vegetables on kids' trays. The law had provided an extra 5 cents for every lunch meal that contained a locally grown component.

Sunday, December 5, 2010

What's for Lunch: Black Bean Burger

By Ed Bruske

By Ed Bruskeaka The Slow Cook

No, this isn't a hamburger, although it looks very much like one. Chartwells at its menu website called it a "spicy black bean burger on a whole wheat roll."

I would love to know where the black been burger came from. I guess I'll have to do some snooping around to find out, since the info isn't posted by Chartwells or the schools.

But here's where it gets even more interesting. What looks like a salad of romaine lettuce and tomato on the side is actually intended as a topping for the burger. And in that plastic cup--what the kids throught was salad dressing--was actually an "ancho sauce" that was supposed to be spread on the burger as well.

I didn't see any of the kids using the salad or the sauce the way. This is where parent volunteers in the cafeteria could help out: coaching the kids on the food and how to eat it. But that doesn't seem to be a particular priority at the moment.

The vegetable on the tray is "herb-roasted potato wedges with shredded carrot." The potatoes, of course, arrive frozen. I didn't see a lot of shredded carrot. Have you ever heard of shredding carrots on roasted potatoes? That's a novel concept, I think.

Here's what the burger looked like with the top down.

Here's what the burger looked like with the top down.USDA Rmoves Roadblock to Michelle Obama's Salad Bar Initiative

The U.S. Department of Agriculture has removed a serious hurdle confronting Michelle Obama’s campaign to place 6,000 salad bars in the nation’s schools after advocates expressed alarm over a government memo indicating that self-serve salad bars would not be permitted in elementary schools.

Backers of the Let's Move Salad Bars to Schools campaign said local health inspectors already were citing the October 8 memo from the USDA’s Child Nutrition Division as a reason for declaring self-serve salad bars a potential food safety hazard and not allowing them around small children.

The memo, signed by Cindy Long, director of the Child Nutrition Division, and circulated nationwide, described only two options for salad bars in elementary schools: salads must be pre-assembled and pre-wrapped, or they must be served by an adult working behind a barrier separating children from the food.

After being questioned by me on these points, Jean Daniel, spokesperson for the USDA’s Food and Nutrition Services (FNS) division, which governs the national school lunch program, said there was a third option not contained in the memo: elementary school children could serve themselves salad as long as the salad bar was designed specifically for small children with a plastic barrier or “sneeze guard” positioned at an appropriate height.

The FNS later issued a written statement, saying, “USDA does not prohibit self service salad bars, and they may be used in elementary schools. USDA encourages the use of fresh fruits and vegetables in school meals. Self service salad bars are one approach that can be successfully included in the meal service when monitored closely to ensure safety.”

An alliance of produce industry, school food professionals, health advocacy groups and government agencies has formed under the first lady’s Let’s Move banner with a goal of placing 6,000 salad bars in schools around the country over the next three years at an estimated cost of $15 million.

Organizers hope to fund the effort through a combination of corporate and private donations, and by creating a website where schools will have individual accounts where they can direct donors from their own communities to make contributions as large or as small as the like.

Ann Cooper, director of nutrition services for Boulder, Co., schools, said she sees “micro-philanthropy” aided by social networking tools on the internet as the cutting edge for funding food improvements in local school districts.

“It’s still a work in progress,” Cooper said. “There’s still a long way to go.” But the project is scheduled to begin accepting applications from individual schools on Jan. 1, 2011. “We’re expecting thousands and thousands of applications,” said Cooper, who estimated there are at least 80,000 schools in the U.S. without salad bars.

The salad bars in question, made of polyvinyl and chilled with ice packs, cost $2,500 each. “If a school found 500 people to each donate $5, they could have a salad bar,” Cooper said. Any school that participates in the national school lunch program is eligible to apply. They must show that the local schools superintendent, the school principal and the food services director are committed to using a salad bar on a daily basis. Preference will be given to schools with large numbers of low-income students, and those that have achieved at least the bronze level in the HealthierUS Schools Challenge.

"The coalition is absolutely raising money to donate salad bars and we fully expect to raise a significant amount of funds," said Cooper. "We assume that all schools will have some amount of money donated directly from the coalition and some schools will have their salad bars fully funded."

Cooper recently was involved in a similar campaign in which Whole Foods garnered $1.4 million in donations from its customers in order to donate salad bars to schools. Cooper's Food, Family, Farming Foundation, based in Boulder, will be in charge of managing the application process for the Let's Move campaign.

Another principal partner in the Let’s Move alliance is United Fresh, a produce industry trade group, that began its own salad bar campaign two years ago backing legislation sponsored by U.S. Rep. Sam Farr (D-Calif.) that called on the USDA to increase fruits and vegetables in school meals. Farr represents the produce-rich Salinas Valley.

Ray Gilmer, spokesman for United Fresh, said the legislation “never got much traction,” but generated some buzz around salad bars. A year ago, United Fresh began soliciting donations from its corporate members to purchase salad bars and place them in schools. “A lot of companies want to place them in the communities where they operate, a sort of ‘good neighbor’ thing,” Gilmer said.

Gilmer said the United Fresh campaign was low-key, conducted mostly by word of mouth and through internet chatter. To date they’ve given away 60 salad bars and plan to donate a undetermined amount of cash to the Let’s Move campaign. "We're going to New Orleans for a convention, and we’ve already placed 10 salad bars in schools there," Gilmer said.

A third partner in the White House effort is the National Fruit and Vegetable Alliance, composed of the USDA, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and such disparate groups as the American Cancer Society and the California Department of Public Health.

The CDC has emerged as a leader of the group, taking up fruits and vegetables as a key ingredient to preventing diet-related diseases such as obesity and Type 2 diabetes.

The salad bar effort still faces some obstacles. Some schools don’t want salad bars. Montgomery County, just outside the nation’s capitol, does not permit salad bars for food safety reasons. Philadelphia schools similarly do not offer salad bars, but serve salad in the regular food line instead.

“Self-serve brings a number of management issues that we’d have to look at,” said Philadelphia schools spokesman Fernando Gallard. “Basically, you’d have a salad bar in an open area where people are going to walk around it. That’s something we still have to consider, the sanitation issues.”

Ann Cooper has complained about USDA regulations that require students who use the salad bar as a component of a reimbursable meal to pass a cashier or point of sale station where a trained cafeteria worker would inspect the student’s tray and confirm that the student had taken the required items in the correct portion sizes. Cooper said such rules can create a logjam in the cafeteria.

Here in the District of Columbia, many food service areas are not designed to accommodate a salad bar. Installing one would require rethinking how students pass through the meal line and where the cashier is situated.

Kate Adamick, a school food consultant and fervent salad bar advocate, said those obstacles can be overcome without too much difficulty. "I don’t think there’s any other way to serve produce in school," she said. Most cafeteria vegetables are cooked to death or come out of a can and kids either refuse them in the service line or throw them in the trash. Adamick believes children eat more vegetables when they're allowed to serve themselves from an array of fresh choices. "When kids get to make their own decisions, they’re much more likely to try things."

Saturday, December 4, 2010

Kids Make Portuguese Salt Cod Casserole

By Ed Bruske

aka The Slow Cook

Before refrigeration, fisherman plying the rich Atlantic waters off Canada dried and salted their harvest of cod. The cod are mostly gone, but the tradition lives on, nowhere more so than in Portugal, where there are said to exist at least 1,000 recipes for preparing salt cod.

Salt cod isn't exactly a convenience food. You have to soak it at least 24 hours in several changes of water to remove the salt and rehydrate the flesh. But I couldn't very well take my food appreciation classes to Portugal on our virtual world culinary tour without sampling at least one salt cod dish, and this casserole--simple as it is--remains a classic.

The first order of business is finding the salt cod. I purchased mine at our neighborhood Harris Teeter where it comes pre-boned in this nifty wooden box. I'd never heard of salt cod from China before. But perhaps that's where they're sending the fish these days to be processed. You can also find it in ethnic groceries, any catering to Latin, African or southern European clientele are a good bet. Normally I wouldn't think of eating Atlantic cod. It's been so overfished, the Monterey Bay Aquarium's Seafood Watch program advises consumers to stay away from it. But you can't very well make a traditional Portuguese salt cod dish without it.

To make enough to feed a family of four, soak 8 ounces salt cod in a covered container, refrigerated, for 24 hours, changing the water three times. Remove the cod and place it in a heavy pot, cover it with boiling water and cook over moderately low heat for about 10 minutes, or until the fish flakes apart with a fork. Drain the fish and when it is cool enough to handle, break it into small pieces with your fingers, removing any bones and skin. Set aside.

Meanwhile, peel 1 pound boiling potatoes, such as Yukon gold. Cut the potatoes into quarters lengthwise, then cut these pieces into 1/4-inch slices. Cook the potato slices in plenty of salted, boiling water until just tender. Drain well in a colander.

While the potatoes are draining, brown one yellow onion, cut in half and sliced thinly, in extra-virgin olive oil at the bottom of a heavy, oven-proof skillet. When the onions have caramelized and smell quite delicious, remove them from the skillet and brown the potatoes in the same fashion, adding more olive oil as needed.

Remove potatoes from the heat. Add the browned onions back to the skillet along with the flaked fish and a small handful of chopped fresh parsley leaves. Toss everything together and place in a 350-degree oven for about 20 minutes, or until the fish has lightly browned and the casserole is sizzling hot. Garnish with pitted, oil-marinated black olives, chopped hard-boiled egg and a little more chopped parsley.

This makes a simple supper, but oh so good. And there's plenty of handwork-slicing onions and potatoes, flaking fish, pulling parsley leaves--for the kids to do. Just be sure to have extra olives on hand. The kids really go for those.

Friday, December 3, 2010

Help Save Healthy Schools Funding

As you probably know, the landmark DC Healthy Schools Act was unanimously passed into law earlier this year, and fully funded with a 6% sales tax on soda. But Mayor Fenty proposed in his Budget Gap-Closing Plan to eliminate $5.2 million in the FY 2011 budget for the DC Healthy Schools Act, and to delay implementation of the Act indefinitely.

We need your help! Please take a moment to join the D.C. Farm to School Network in telling the DC Council to reject the Mayor’s proposal, and ensure that the Healthy Schools Act is fully funded in the current Fiscal Year budget.

Just take these three, easy steps:

1) Sign-on as an individual or organization to our letter urging Councilmembers to fully fund the DC Healthy Schools Act.

2) Call your Councilmember during our Phone-In on Monday December 6th, between 2:00 and 4:00 p.m.

a. Share how you have been affected by the DC Healthy Schools Act, and why you think it’s important. For example, you can say: “I am a resident of Ward X, and I ask that the Councilmember ensure the full funding of the DC Healthy Schools Act in the Fiscal Year 2011 budget.” Follow this link to find your ward.

b. Tell them: “I also believe that DC Council should take a balanced approach to closing the budget gap – it should choose to raise revenue rather than cut the Healthy Schools Act and other vital programs like Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF), Adult Job Training, Grandparent Caregiver, Childcare Subsidies, Interim Disability Assistance, and the Local Rent Supplement Program. As a taxpayer in the District, I encourage the Council to vote for a one percent income tax increase on income above $200,000 to help fund these programs.”

3) Email your Councilmember directly to tell him or her you fully support the Healthy Schools Act and a balanced approach to closing the budget gap.

Share this Action Alert with your networks. We must act now! The Council will vote on the Budget Gap-Closing Plan on Tuesday, December 7.

Thank you for your continued efforts and support.

Thursday, December 2, 2010

Child Nutrition Act Passes, But Don't Expect Better School Food

By Ed Bruske

aka The Slow Cook

On Thursday afternoon, the House approved the "Healthy, Hunger-free Kids Act," also known as the child nutrition reauthorization (CNR) bill. Having already cleared the Senate, the bill is ready for approval by President Obama, who has long supported it (along with Michelle Obama, who's made kids' health her policy focus). This broad piece of leglslation, which Congress has to reauthorize every five years, controls funding for all child nutrition and women, infant, and children (WIC) programs, including school lunches.

The reauthorization had been dogged by delays. The Senate passed it by unanimous consent in August. In the House, the bill bogged down recently because some Democrats recoiled from funding the school lunch budget increase with money taken from the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP): in effect, adding money to low-income children's lunches by taking it from their home meal budgets. But then the White House promised to find a way to replace the money taken from SNAP, and the way was cleared for the successful vote.

Approximately 31 million children participate in the subsidized school meal program, with the federal government giving schools $2.72 for a fully subsidized lunch. According to the School Nutrition Association, the average school loses 35 cents on every lunch it serves.

Unfortunately, while the bill's long-delayed passage is being lauded by sustainable-food advocates, it provides just 6 cents in extra funding. Worse, it calls for new school-food standards that seem destined to jack up costs in the nation's cash-strapped cafeterias while consigning tons more cooked-to-death broccoli, canned green beans, and other vegetables to the trash heap. Meanwhile, the puny 6-cent boost in federal payments for school lunches is conditioned on schools adopting those very same standards.

The extra

Sure enough, the Institute of Medicine, in issuing its recommended standards in October 2009 at the USDA's behest, called for precisely the kinds of things kids like to eat least: bigger servings of whole grains and vegetables. The standards would even make it more difficult for schools to substitute fruits or fruit juices for vegetables, on the theory that kids really need more greens and orange-colored vegetables in their diet.

The IOM panel that made the recommendations said the requirements would certainly raise the price of ingredients for school meals, with no guarantee kids would actually eat the food. Kids have a long history of either refusing vegetables in the food line, or just dumping them uneaten. School kitchens have an equally long history of serving vegetables that are anything but palatable.

So much for Congress coming to the rescue of school food.

On the plus side, the IOM standards would lower the number of calories schools must offer kids in subsidized meals, which could mean fewer sugary options in the cafeteria. Up to now, schools have been using sugar to jack up the calories in their meals in order to comply with outdated USDA requirements.

The IOM panel said it hoped the new standards would help squeeze sugar off school menus. But it tried to leave plenty of room for sugar-laden chocolate milk. They wouldn't want to cross the dairy industry, after all.

With all the hullaballoo over the $4.5 billion cost of the legislation, and whether it would have to be paid for with some $2 billion in funds previously designated for

For years, healthier food advocates have been trying to get candy, chips, sodas, and other junk food out of schools, to no avail. The USDA now has authority to banish any foods (with the exception of those sold at fundraisers) that do not comport with the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, which means limits on fat, sugar and salt.

Does that mean vending machines with baby carrots, not Doritos and Sprite, in every public school? Not necessarily. The fight now shifts to the inner sanctum of the USDA secretary's office, where it is yet to be seen what kind of influence the powerful food industry lobby will wield.

Another large chunk of change in the bill -- $375 million -- is designated to fund grants at the state level for nutrition education and anti-obesity efforts. There's $40 million to study the causes of hunger, obesity, and Type 2 diabetes in children, and a token amount -- $5 million -- allotted for grants to promote farm to school programs, especially in schools with large numbers of low-income students.

Congress also calls on the USDA to study ways of using Medicaid and census data to allow large blocks of children to become eligible for free school meals without filling out cumbersome applications, meaning easier access to food. The bill also orders cafeterias to make water freely available.

This story orginially appeared at Grist.

Wednesday, December 1, 2010

Testifying for Healthy Schools

Given before the D.C. Council yesterday, as it considers removing funds for better school food in the District as part of a plan proposed by outgoing Mayor Adrian Fenty to close a $188 million budget gap.

My name is Andrea Northup and I coordinate the D.C. Farm to School Network, a program of the Capital Area Food Bank. The Network aims to improve child health in the District by increasing access to healthy, local food in school meals.

My message for you today is that the Council must maintain funding in the Fiscal Year 2011 budget for the Healthy Schools Act. Specifically, I urge you to reject the section of the Mayor’s Gap-Closing Plan that calls for elimination of funding and FTE’s for Healthy Schools Act initiatives in the Office of the State Superintendent of Education and the Office of Public Education Facilities Management.

The Healthy Schools Act has attracted national recognition for its comprehensive approach to improving child health and wellness. The Act sets high standards for school nutrition, expands access to school meals, increases physical and health education requirements, and more. For the more than 70,000 children currently attending D.C. Public and public charter schools, the proposed $5.2 million in cuts to Healthy Schools Act implementation would be a major step backward, just as the city is making real strides in its struggle against the rising tides of childhood obesity and hunger.

Half of Washington, DC youth are at risk of hunger, a third live in poverty and over a third of all District youth are obese or overweight. Most get their main meals each day at school, especially during these tough economic times. Hunger and malnutrition have serious effects on child health, cognitive function, growth and development. If left underserved, these at-risk youth will become drains on the District’s dime as unhealthy, unproductive adults. It’s shortsighted not to see the costs that will accrue down the road if we don’t act to address the epidemics of child hunger and obesity NOW.

In May 2010, the Council unanimously enacted the Healthy Schools Act, then approved a 6 percent sales tax on soda to secure an estimated $8 million to fund the Act. We must NOT allow the Mayor to take away this funding that was promised specifically for the health and well-being of schoolchildren in the District of Columbia. Difficult choices must be made in this harsh economy, but the health of vulnerable children in the District must NOT be compromised.

Doing so would counter the recent momentum of Healthy Schools Act implementation. Schools have made serious investments in order to comply with the Act’s strong nutrition requirements, banking on funding incentives in the Act. Healthier, tastier meals are being served in cafeterias city-wide. Schools have re-written contracts with their food service vendors. Jobs have been created as schools replace processed convenience food with from-scratch meals using high quality ingredients. More students are participating in school meals, and parents and students are behind the reforms. Schools CAN NOT sustain changes like these without Healthy Schools Act funding, even though healthier meals been overwhelmingly well-received.

The rest of the nation is watching these changes taking place in the District with a critical eye. Will the Council step up and fully fund the Healthy Schools Act, and prove that we can reverse some of the nation’s highest child poverty and obesity rates? Or will the Council sit idly by as funding promised to D.C. children gets absorbed into the city coffers? Thank you for the opportunity to testify today, and feel free to contact me with further questions.